I believe in using scientific evidence (i.e. available research) to make important health choices. But in my journey with my kids’ eczema, I have also been humbled to understand that for as much as we know, we still don’t know everything. Throughout the telling of our story on this site, I have talked about how the most effective generally accepted treatment offered to us by our physicians (i.e. constant moisturizing coupled with potential lifelong dependence on steroids) temporarily fixed and was better than having broken, painful, itchy skin … but still fell so sorely short of a cure or true solution. Living through this experience with my children expanded my mind and the way in which I go about making health decisions and evaluating available treatment options offered to me.

I used to adopt without question every treatment option proposed by evidence-based medicine. Now, I live in the grey area between believing in evidence and evidence-based medicine, utilizing and implementing generally accepted treatment plans, and engaging in a two-way and patient-centred dialogue with our physicians … WHILE STILL acknowledging that what we do today as “generally accepted treatment” may change tomorrow as our research knowledge gets better. I leave the door open for the near certainty that we do not yet have all the answers, and that true cures — not just today’s pharmacologic or surgical solutions for symptom control — are still possible from exploring at the frontiers of what we know. And finally, I now readily acknowledge that many of today’s generally accepted treatments carry with them side effects that need to be soberly considered and weighed out, especially if the treatments are merely treating a symptom and not preventing or curing the disorder.

The idea that what we do today as “generally accepted treatment”, or even that our understanding of a disorder, may be wrong, and the medical community’s potential to limit progress in their understandable zeal to guard practise within existing evidence-based confines is highlighted well in Dr. Barry Marshall’s story. Dr. Marshall’s experience in elucidating the true cause of stomach ulcers also serves as a sobering reminder that sometimes we must explore at the frontiers of what we know in order to solve medical mysteries — and that not everyone exploring at the frontiers, at the limits of our comfort level, should automatically be written off. (See Dr. Marshall’s brilliant and inspiring story in the Discover Magazine article entitled, “The Dr. Who Drank Infectious Broth, Gave Himself an Ulcer, and Solved a Medical Mystery (The medical elite thought they knew what caused ulcers and stomach cancer. But they were wrong—and did not want to hear the answer that was right.)”.

When I departed from the generally accepted solution of potential lifelong steroid dependence for my children, I departed carefully, thoughtfully, and while staying in close contact with our physicians, and I made environmental changes that are generally regarded as safe (GRAS). Because of the anecdotal evidence that the solution worked, I was convicted that the impact of detergents now ubiquitous in our modern environments and its potentially causative role in eczema (theory presented by A.J. Lumsdaine on solveeczema.org) needs research validation. Unfortunately however, I neither have the resources nor ability to fund or personally complete the research I so desperately think is needed.

This leads me to the biggest dilemma I believe is faced today in health care research: The dilemma of the citizen scientist.

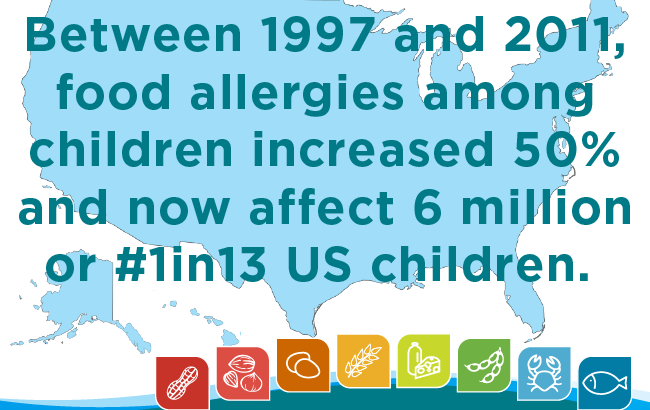

What if some of our most difficult, seemingly intractable, medical problems of today cannot be solved unless the paradigm in which we imagine and create solutions drastically changes? And what if that paradigm shift cannot occur unless individuals who haven’t grown up within the existing research “club” are able to challenge norms, bring new ideas, or otherwise contribute as equal partners? Or what if we are limited from solving these most pressing medical problems of today because even how we conduct research (often a controlled, laboratory setting) is what limits us? For instance, I would argue that medical problems with a significant environmental component or causation are difficult to study and solve within controlled, laboratory settings and may require a different type of data gathering that is more distributed — even crowd-sourced — and lends itself well to the burgeoning field and approach of “citizen science”.

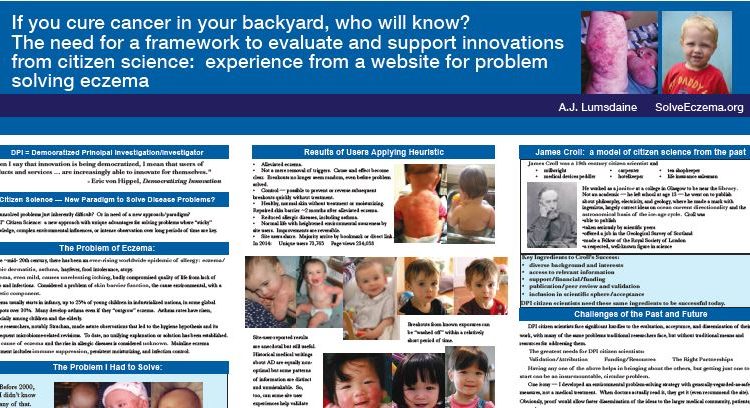

The author of solveeczema.org, A.J. Lumsdaine, presented a poster at the Citizen Science Association’s 2015 Conference getting at the need for mechanisms or frameworks to evaluate and therefore validate innovations from Citizen Science. Without these frameworks, we run the risk of dismissing innovations that are exploring at the frontiers of what we know, and may hold promise for future solutions and cures, or disallowing innovators from participating in research initiatives as equal contributors.

Have a look at Lumsdaine’s poster, entitled, “If you cure cancer in your backyard, who will know? The need for a framework to evaluate and support innovations from citizen science: experience from a website for problem solving eczema”.

Incidentally, my child is one of the children in the before-and-after pictures on the poster which show the dramatic efficacy of Lumsdaine’s problem-solving heuristic and demonstrate strong anecdotal evidence to support her theory about the impact of detergents on eczema. There are a number of other children from literally around the world whose dramatic before-and-after photos on the poster are remarkable.

I welcome any thoughts on how citizen scientists can be co-opted either for idea generation, data gathering, data validation, or their innovative ideas — into the traditional research space. I look forward to innovations in the domain of research itself and the hope of new ways to move towards solving the most intractable, challenging medical problems we have today!